|

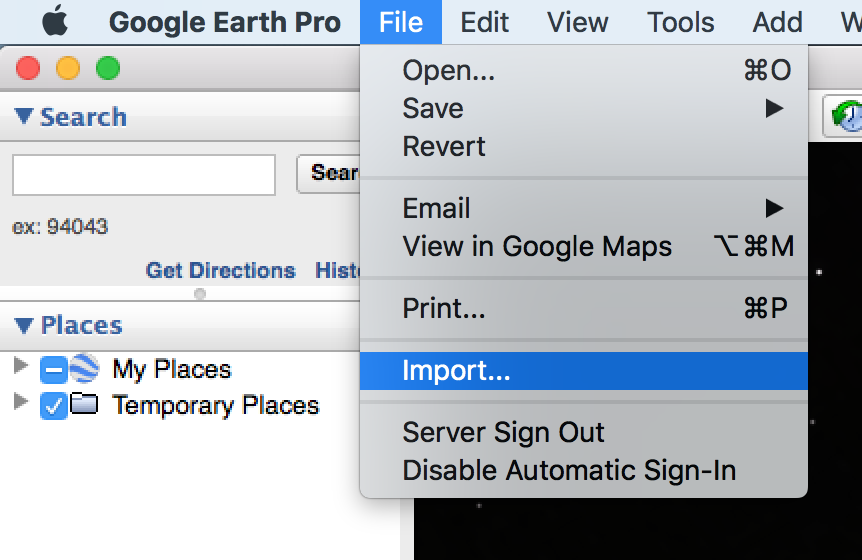

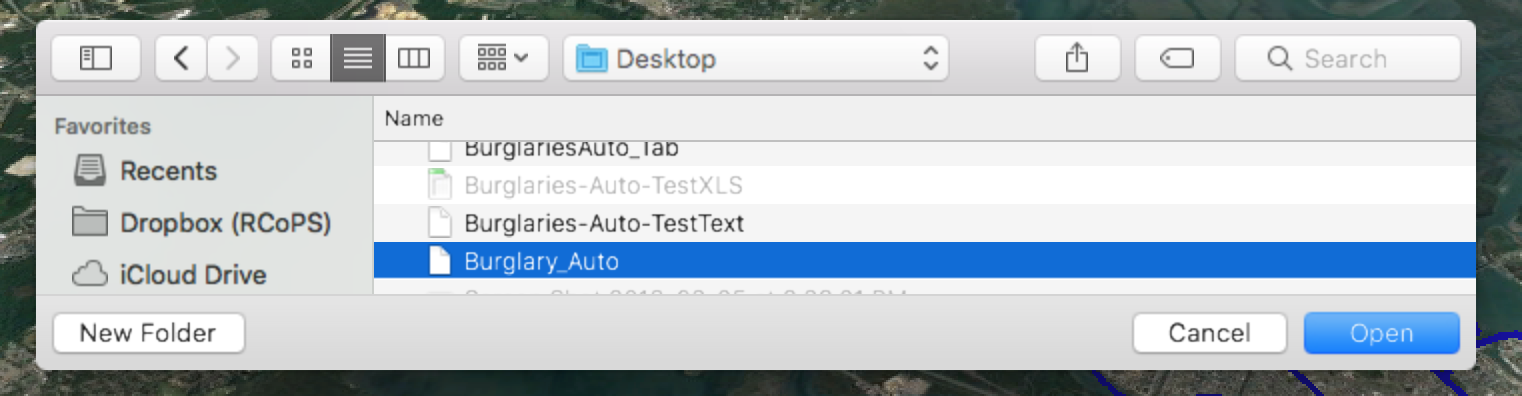

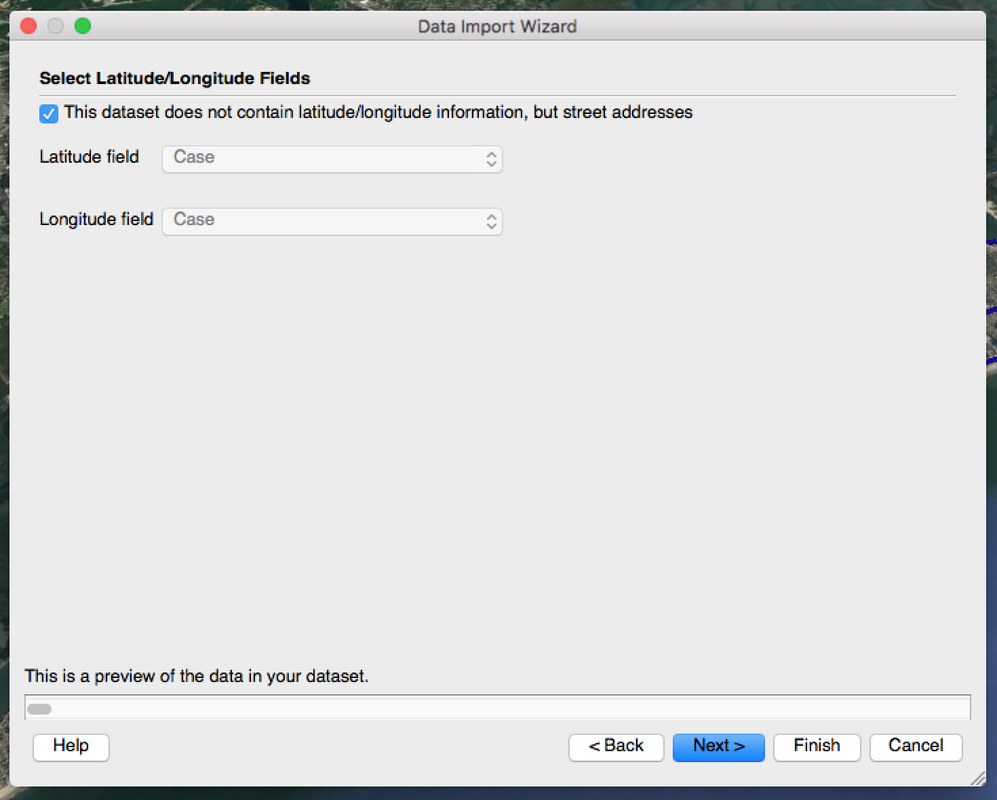

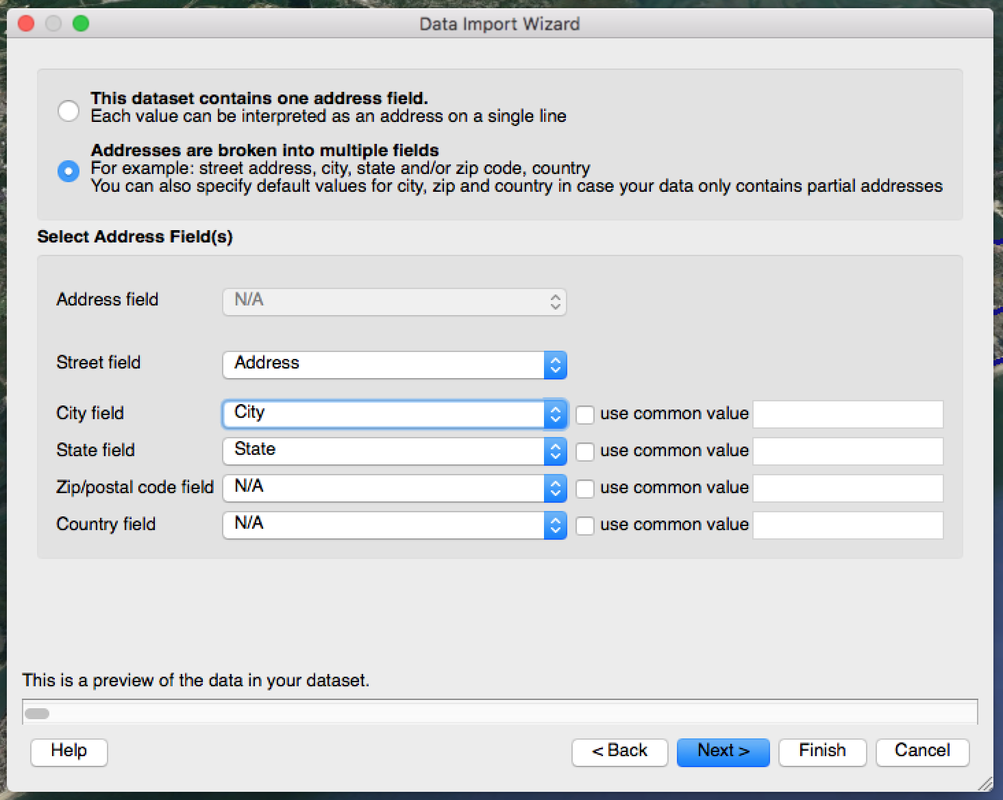

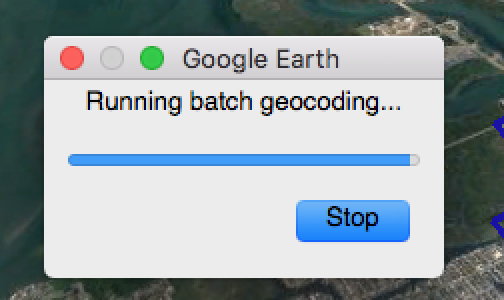

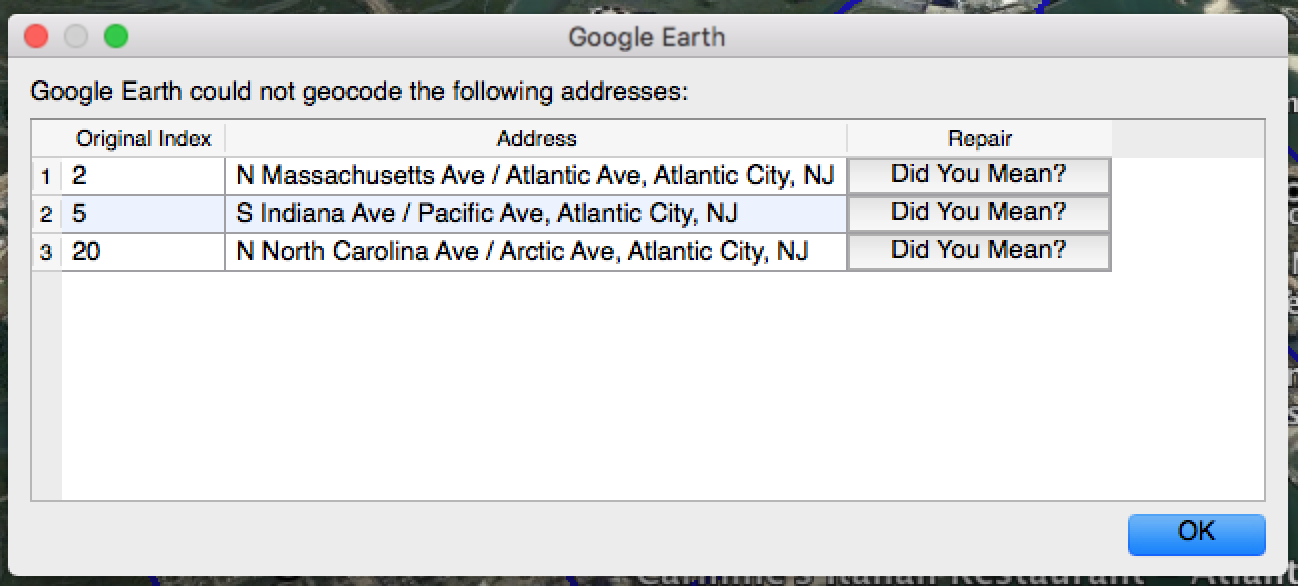

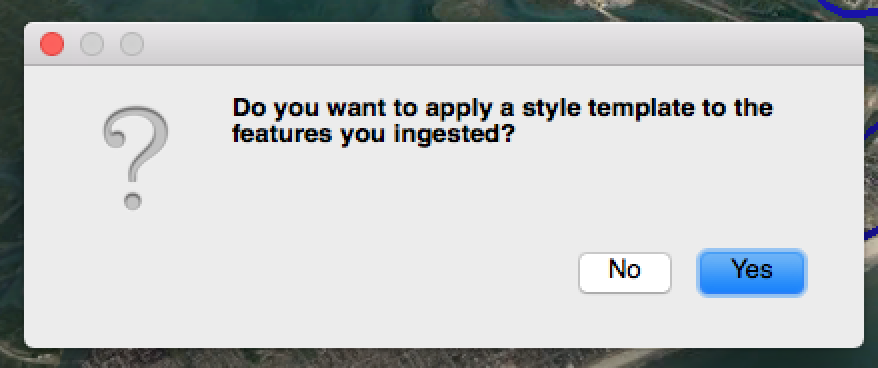

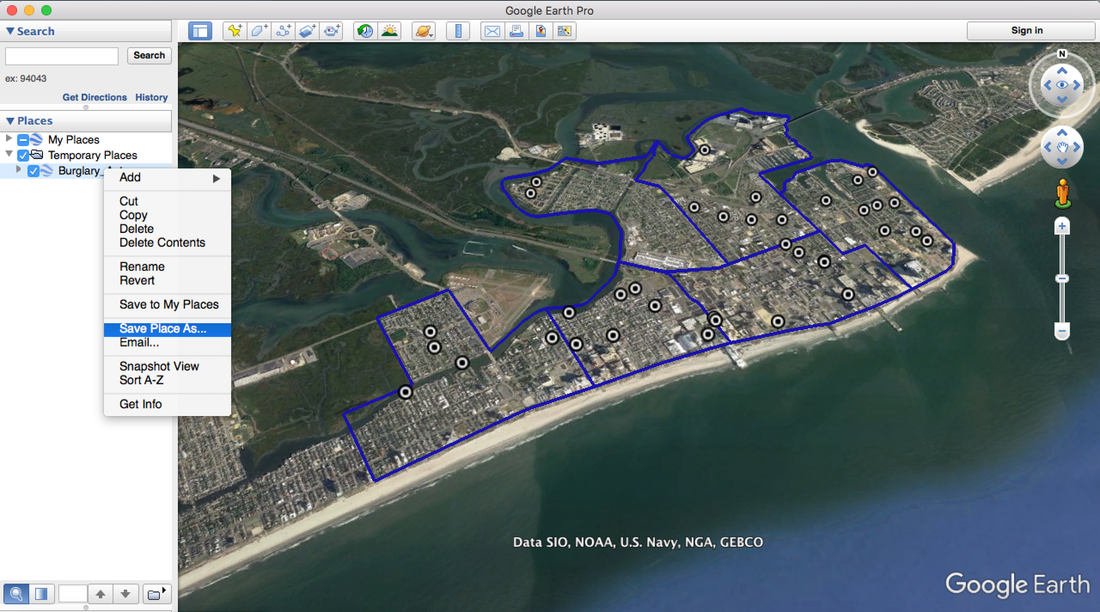

Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) requires geo-referenced data that are often contained in tables, like spreadsheets or CSV (comma delimited) files. Geocoding is the process of transforming these data tables with descriptions of locations, such as addresses or XY coordinates, to locations on the Earth's surface. Common formats of outputs from the geocoding process are shapefiles (.shp) and KML/KMZ map files that can be viewed in a GIS (Geographic Information System), such as QGIS, or used for spatial risk analysis, such as with the RTMDx software. There are many batch geocoding services on the internet; some are free and others charge fees. Here we present a readily accessible and free geocoding option. You can easily geocode your data tables, export the feature points as KMZ files, and then use them for Risk Terrain Modeling. Check this out (7 steps): 1. Open Google Earth Pro on your computer. It's free to download. 2. Click "File" from the menu at the top of the screen, then "Import..." 3. In the dialog box that appears next, select a CSV (comma delimited text) file to import and then click the "Open" button. This will be your data that has addresses or XY coordinates as one of the attributes. Note: Your data should contain street address, city, and state as their own columns. If you have XY coordinates, they should be in two separate columns. 4. Follow the on-screen instructions in the "Data Import Wizard". Click the "Next" button to proceed through the steps. Be sure to set the "Street field", "City field", and "State field" accordingly. 5. After you click the "Finish" button in the Data Import Wizard (previous step), you may see a notification that the batch geocoding is in progress. Let it work. If addresses could not be geocoded, a dialog box will appear allowing you to review and repair the addresses. 6. When geocoding is complete, you'll be asked if you want to "apply a style template to the features you ingested?" This lets you adjust symbology, colors, etc. It's optional, and up to you. For this example, I clicked "No". 7. Now you should see a points on the screen and a map layer appear in the table of contents under "Temporary Places". That's your map with geocoded data. You can zoom in/out, etc. You can right-click on the map layer and select "Save Place As..." to export a KMZ file. Now you have the map on your computer that you can share or upload to the RTMDx software to use for Risk Terrain Modeling. You may also want to try geocoding in QGIS, a free and open source Geographic Information System. Here's how: www.gislounge.com/how-to-geocode-addresses-using-qgis

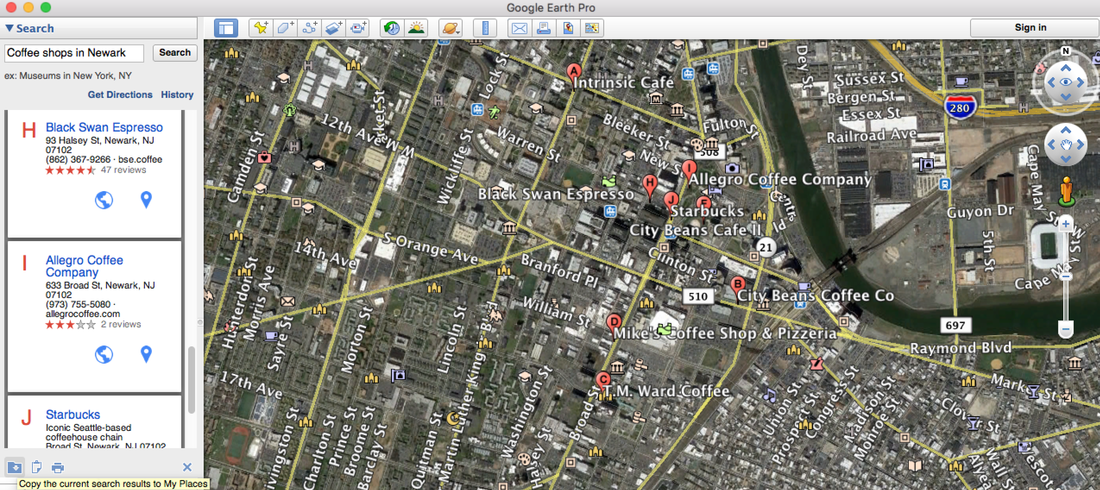

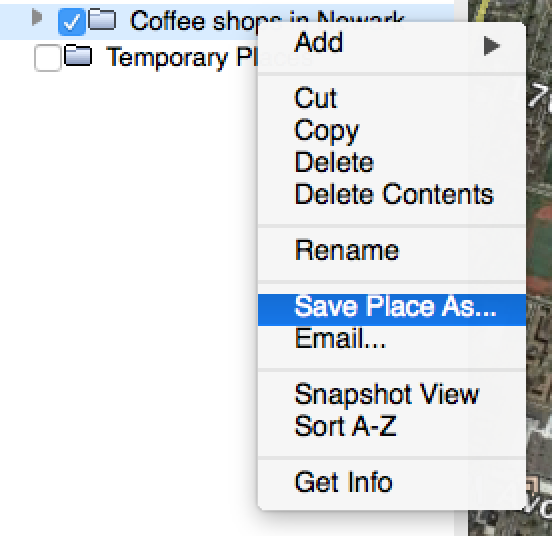

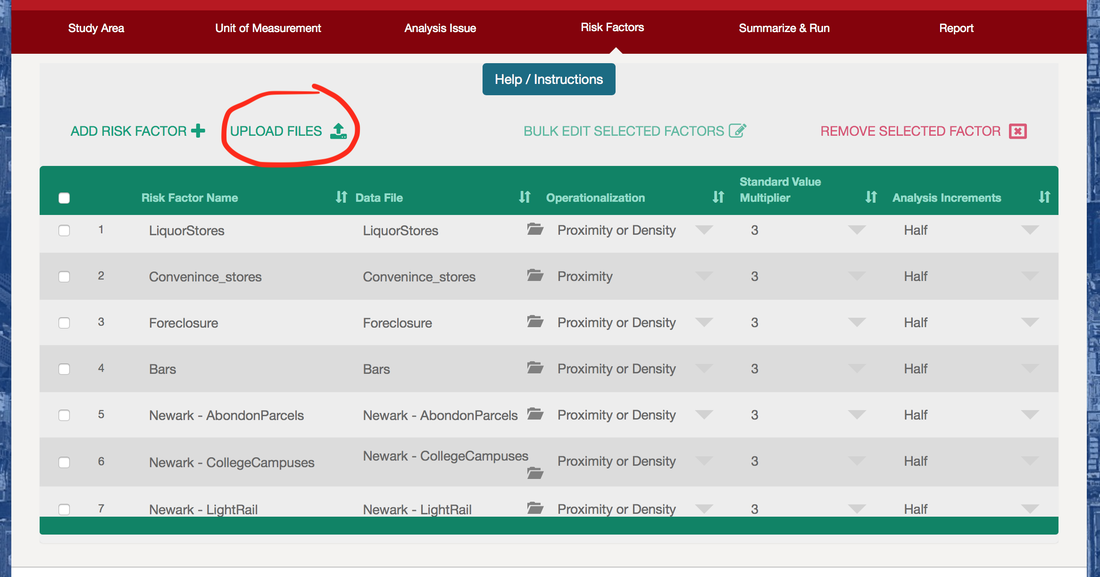

Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) analyzes crime patterns to identifies features in the environment that attract criminals and enable their illegal behavior. (RTM is also used for other types of events and human behaviors, but that's a discussion for another blog post). The RTM diagnosis makes very accurate forecasts of places where resources get deployed in order to intervene -- to reduce risk and prevent crime. Many physical features make up a landscape, and the way they co-locate or interact in space can influence behaviors, events and outcomes. Here is a starter list of environmental features that could be considered for testing with RTM, such as fast food takeout, convenience stores, rooming houses, coffee shops, schools, alleyways, and so forth. There are many sources to get these datasets, including your own/agency CAD/RMS systems, open data portals, local government records, or business directories. We want to share another option: Google Earth Pro. In Google Earth, you can search for place features and then export the feature points as KMZ files. Then you can easily use the KMZ files for Risk Terrain Modeling in the RTMDx software. Check this out (5 steps): 1. Search for the places (i.e., risk factors) of interest. E.g. "Coffee Shops in Newark" 2. A list appears and the points appear on the map. 3. Click the small folder icon to "Copy the current search results to My Places" 4. In Google Earth, with the search results map layer in your My Places table of contents, simply right-click on the layer and select "Save Place As..." 5. Open the RTMDx software and click the "Upload Files" button to add your newly acquired risk factors in KMZ format. Then run your RTM analysis.

We’re frequently asked how to get started with Risk Terrain Modeling and the RTMDx software. Here’s an overview:

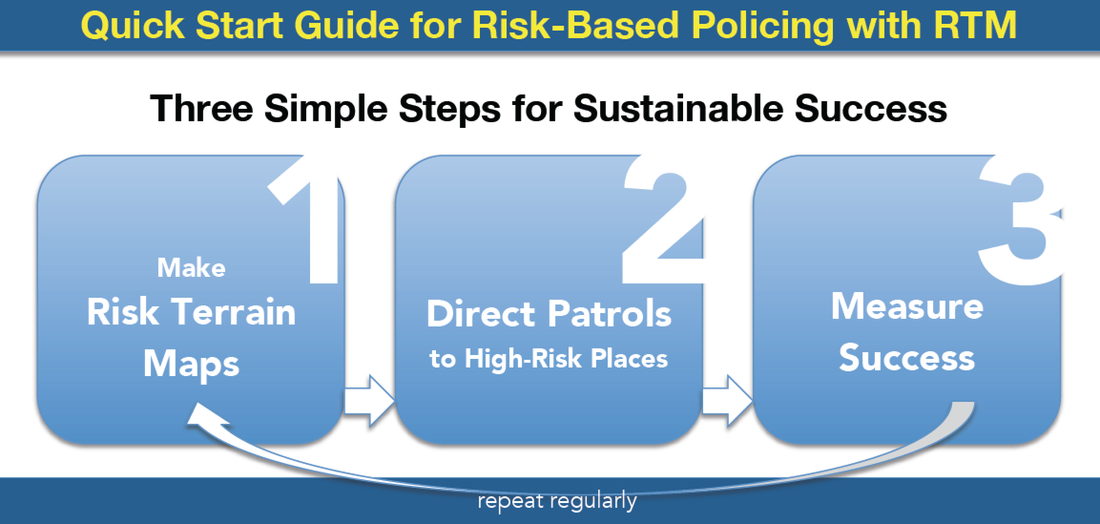

The RTMDx software is delivered to you through secure login, allowing easy access by all of your project partners and stakeholders while you remain in full control of your data. It's easy to use and priced under $5,000 (that's it! ...no other costs or fees). Rutgers University developed this evidence-based software with support from the U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. Check out the click-through tour for an overview of the software's interface. Contact the Rutgers Center on Public Security for questions or to schedule a live demo: info@rutgerscps.org With RTMDx, Risk Terrain Modeling is straightforward. Deliver actionable information quickly and easily. To see some of the ways it has been used to support police patrols, investigations and crime forecasting, check out this YouTube video. Crime prevention and risk reduction initiatives meet your local needs and expectations. The most common form of implementation follows 3 basic steps. This Quick Start Guide (PDF) lays them out simply. Once you’re comfortable with the basics, you can build on them to expand risk-based policing operations and improve coordination among other stakeholders. RTMDx software serves as more than just an analytical tool for Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM). Reports and maps help to focus resources at high-risk places. Here are 4 short case studies as examples. Here's the annual report from the risk-based policing initiative in Atlantic City (with crime drops over 36%). RTM with RTMDx keeps problem-solving efforts grounded, and evidence-based. It adds context to ‘big data’. It informs decisions for deploying resources and directing strategies efficiently. Here are some of the many other benefits. Click here to get started with RTM. RTM Meets All of These Requirements1. Data used in the analysis should be reliable and valid (i.e., content and construct validity). The data sets and their sources should allow for replication and continued forecasting. This includes the requirement that the forecast technique does not rely heavily on the outcome of interest (i.e., the dependent variable) to be the predictor (i.e., independent variable). Such a forecasting technique would not be sustainable if it were both actionable and successful since outcomes would ultimately be prevented.

2. The outputs of the forecast should be operational. It should be reasonably clear what to do with the information to respond to the forecasted effects. Knowing where to go is a start. But forecast outputs should also inform decisions about what to do when you get there. 3. The method of the forecast should be operationalized consistently from one instance to the next. Data sets and sources may change, as will analysts, etc., but the reliability of the forecasting method must withstand multiple iterations, in different settings, by different people, and for different types of outcome events. 4. The elements of the forecast should be articulable, with the importance of each factor relative to one another directly measured. The direct impact of key factors on outcomes should be demonstrable (i.e., internal validity). 5. The output results should be within a range of reasonable expectations (i.e., face validity). The forecasting process should be able to justify why a result was produced or else the forecasting process should be able to be revised in a non-arbitrary way. 6. The method of the forecast should be able to tolerate the products of successful interventions. Especially those that are based on the intel from prior forecast iterations. Basically, any successful forecast should yield valuable information that can be operationalized for preventative action. However, if the preventive action is successful at reducing crime incident counts and/or changing their spatial patterns, then it could directly affect the precision/accuracy of future forecast iterations. This is why a successful forecasting technique should be able to tolerate the products of successful interventions. Police agencies live under the constant threat of being too successful. This statement is a bit pretentious and a lofty goal that is difficult to achieve. But let’s face it; crime problems fuel police agency budgets. When crime problems emerge and can be articulated, police executives demand more resources to respond. When police achieve measured and sustained crime reductions, it becomes more difficult for departments to justify the need for more officers, technology, or other resources. Police agencies live under the constant threat of being too successful. Successful policing is often taken for granted when crime counts are low – even if police activities were initially credited with reducing crime. Unfortunately, a disconnect between inputs and outcomes of policing occurs when measures of police productivity are reliant on the persistence of the crime incidents that police departments aim to prevent. Such is the case when productivity measures depend on people to be stopped, ticketed or arrested for crimes already committed rather than on more sustainable and benign measures, such as police officers’ efforts associated with reducing crime risks, or other actions taken to mitigate spatial or situational attractors of illegal behavior at risky places. Police actions have an important role to play in affecting crime risks. They can deter offenders, embolden victims, and assist in the hardening of targets. These products can have the overall impact of reducing crime occurrence. But we must separate what we would see as crime prevention and response from risk reduction strategies. A risk reduction strategy requires that police identify the environmental conditions in which crime is likely to appear. This diagnosis can be ascertained from existing free resources, such as risk terrain modeling. Police can then propose strategies to address these conditions and interrupt the interactions that lead to illegal behavior settings and new crimes. Alternatively, police dealings with people at crime hot spots may have the effect of deterring criminals or even reducing crime counts at these areas in the short-term. But, despite this, the underlying spatial factors that attract and generate problems in these areas do not go away. So, three things can happen: crime disappears, it displaces, or it subsides to reemerge later. This is “good” for justifying police budgets, but it's a burden on police departments in pursuit of the mission to prevent crime with sustained oomph. Sparrow (2015) wrote a provocative article about measuring performance in a modern police organization. He argues that reported crime rates will always be important indicators for police departments. However, substantial and recurrent reductions in crime figures are only possible when crime problems have first grown out of control. A sole reliance on the metric of crime reduction, Sparrow explained (p. 5), would “utterly fail” to reflect the very best performance in crime control practices when police actions are successful at keeping crime rates low and nipping emerging crime problems as they bud. Beyond looking at crime rate changes, a risk reduction approach to solving crime problems suggests success from interventions when factors other than merely crime counts improve. Risk-based policing has dual objectives: One to reduce crime counts and the other to reduce the influences of known risk factors. Risk-based policing allows police leaders to demonstrate to elected officials and budget-makers how what police are doing works to reduce crime and why the crime rates are lower because of their efforts. While risk-based policing can accommodate the ideas of situational crime prevention in targeting certain locations for intervention, the ideals extend beyond a focus on opportunities for crime or the “crime triangle”, and, instead, target all aspects of the context that raises the risk that crime will occur. This opens the door to a broad array of police productivity and success measures that do not demand the illegal behaviors to continue, or crime incidents to be reported, in order for police to validate or justify their own value and continued budget-item existence. Risk terrain modeling, for instance, provides an approach to understanding crime occurrence by identifying the relative influences of factors that contribute to it; risk terrain maps inform decisions about which places can be targeted to reduce these risks. This is inherent in risk-based policing, which considers the effects of guardianship, victim characteristics, locations, precipitators, exposures, and offenders in a risk narrative that is contextually dynamic. Iterative risk terrain models and reconsiderations of risk narratives make risk reduction activities transparent, measurable and testable. In this way, risk-based policing enables police departments to be appropriately credited with success and judged against the probable consequences of alternative or non-existent engagements in the communities they serve and protect. risk-based policing enables police departments to be appropriately credited with success and judged against the probable consequences of alternative or non-existent engagements in the communities they serve and protect. Cultural shifts within police departments away from ‘crime fighting’ and toward ‘risk management’ costs very little financially. Coupled with sustainable investments in human capital, smart data, continuing education, and current technology, risk-based policing can go a long way to help agencies fight and prevent crime, and then to credit their actions with success in a way that is obviously clear and sustainable. Recent uses of risk terrain modeling in various practical settings suggest that police departments are able to incorporate risk management into their analytical and cultural frameworks with real success. More departments should follow their lead, and city councils should support their efforts.

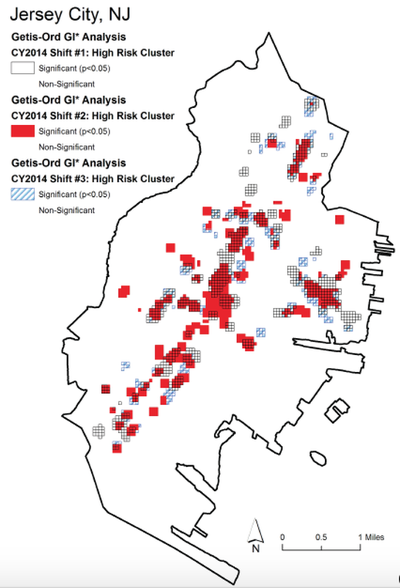

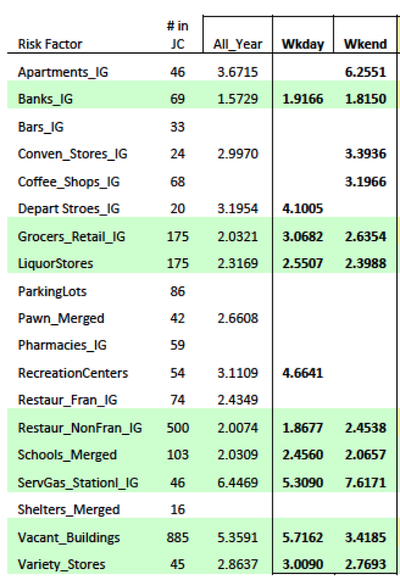

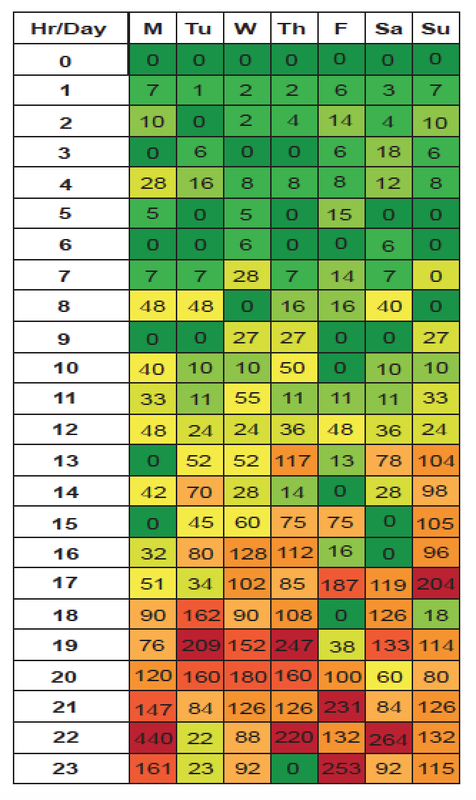

Grubesic and Mack (2008) argued that we cannot treat space and time as independent entities, but, rather, as interdependent ones that interact to create situational risks. The interactions among people and their geographies are deeply fluid in the sense that no feature retains its “social relevancy” permanently (Kinney, 2010, p. 485). Places can be “fantastically dynamic” (Jacobs, 1961/1992; p. 14). Basically, places can have different risks at different times because a criminogenic feature of the landscape can have varying spatial influences depending on its social relevancy at different times and under particular circumstances (e.g. Gaziarifoglu, Kennedy, & Caplan, 2012; Irvin-Erickson, 2014; Yerxa, 2013). The RTM approach allows not only an assessment of risk factors at certain places, but an ability to judge their effects at different times. To do this with the RTMDx Utility, simply prepare your data by first (1) isolating crime incidents (i.e. the events you wish to study) that occurred within the time period(s) of interest to you. Then (2) produce risk terrain models for each of the temporally different datasets. For example: create three shapefiles of robberies that occurred between 7pm-3am, 3am-11am, or 11am-7pm, respectively. Then, use these three datasets to run three different risk terrain models. Something similar can be done to study risky places for crimes occurring on the weekend vs. weekdays; daytime vs. nighttime hours; school year vs. summer months; sporting (home) game days vs. (away) game days; etc.

* Glossary (see the full RTM glossary, here)

For references, see Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; UCPress), by Caplan & Kennedy.

Criminologists have long sought to explain why crime occurs at certain places and times. These inquiries have led to observations and documentation of many different factors that contribute to the spatial and temporal dynamics of illegal behavior and crime victimization. Victims and offenders have been considered in various contexts, formed by both the activities that individuals pursue but also by the nature of the environments they occupy. Some places, we know, are more likely to be locations of crime than others. That is, where exposure to crime events is relatively high. This may be the case because of the characteristics of people who frequent these places or it may have something to do with the qualities of the environments themselves. Of course, both of these can vary by time of day, week, or year. If we concentrate on the characteristics of places, we can focus on factors that are conducive to crime occurrence, offering a means by which to target certain places that are more likely to promote illegal behavior.

Multiple approaches to studying spatial crime risks have merit, and have helped create a more complete picture of the underlying processes that contribute to crime occurence. Analytical models are tools for the acquisition of knowledge. "Knowledge," said Daryl Morey, the man hired to empirically minimize uncertaintly in basketball, "is anything that increases your ability to predict the outcome" [1]. Predictive crime models allow criminologists to explore attributes that lead to crime outcomes, and to determine how much weight to give to each. Having prediction models without any human opinion can force people to ask the right questions. Models may not be the "right" answer so much as the "better" answer, and, thus, can lead to better and more insightful questions. Crime prediction needs more than big or little data. It needs people and experts. Crime prediction models must, at some point, invite human judgement into decision-making processes. The task of the criminologist is not simply to explain empirical results via theory or opinion, but to provide actionable prescriptions for how to use knowledge to combat crime and its consequences. The task of the criminologist is to facilitate and moderate human judgements into decision-making. The talent of a skilled criminologist is to listen to both empirical evidence and subjective human judgement, and to blend the two. A person's understanding of what is seen or heard changes with the context in which each is aquired. The criminologist's mind needs to be in a constant state of defense against all the junk that's trying to mislead it, and to relate context to data without being overwhelmed by the context of data. The criminologist's task is to communicate meaning out of the signals and noise, and to soundly advise how to monitor connections to crime, how to assess spatial vulnerabilities, and how to act in order to reduce the worst effects of their predictions. Post inspired by Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; UCPress), by Caplan & Kennedy and by "The Undoing Project" by Michael Lewis. Endnote from pg. 31 of "The Undoing Project" by Michael Lewis. In our various collaborations with researchers and practitioners throughout the world, we learned… realized… from multi-city projects that the spatial dynamics of crime are not the same in different settings, even for similar crime types. Standard patterns of crime cannot be expected across study settings. Think about this through the analogy of a kaleidoscope. The kaleidoscope itself represents the particular environment, or study setting, that we are interested in examining (see Figure). The pieces of the kaleidoscope (i.e. the glass and the cylinder) are similar from one time to another. The mechanisms for bringing the pieces together in certain patterns (e.g. gravity, the roundness of the cylinder) operate constantly, and the characteristics of the pieces (color, value) are the same from one turn to another. The patterns that are formed, however, change with different combinations of the pieces. So, it is with crime locations that the shards of glass represent features of that environment, such as bars, fast food restaurants, grocery stores, etc. that could attract illegal behavior and create spatial vulnerabilities. Moving from study setting to study setting represents a turn of the kaleidoscope whereby the pieces come together in different ways, creating unique spatial and situational contexts that have implications for behavior at those places.  Figure: The crime risk kaleidoscope illustrates how unique settings for illegal behavior form within and/or across jurisdictions as pieces come together in different ways, creating unique spatial and situational contexts for crime, as depicted by the triangular or hexagonal outlines in the figure. When we diagnose the underlying characteristics of “hot spot” areas across jurisdictions, we realize that the characteristics of places where these crime incidents are occurring in each city are very different. As evidenced by this study, detailed in the forthcoming book, Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; Univ. of Calif. Press), even though crime problems can cluster within cities, the ways in which features of a landscape come together to create unique behavior settings for crime is not necessarily generalizable across cities.

Mindful of the kaleidoscope metaphor, it is not safe to assume that a “standard” response to crime problems will provide similar returns across all environments. This is true for areas within jurisdictions and also across jurisdictions. So one crime problem, such as robberies, will not necessarily respond to a “1-size-fits-all” intervention strategy (even if the strategy worked elsewhere). Behavior settings differ, so interventions need to be tailored accordingly. Risk terrain modeling facilitates this custom analysis of crime problems at various geographic extents. 1. Have clearly defined target areas that are distinctly identified as high-risk.

2. Risk factors in the target area should be clearly identified so the intervention activities can focus on these risks. Let the IPIR inform strategies that tell police what to do when they get to the target areas, not just where to go. 3. Develop strategies for both action and analysis. Risk is dynamic. The very presence of police in an area changes the risk calculation for both motivated offenders and potential victims. Utilize analysts to consider opportunities for tactical applications of intervention strategies – e.g., at specific times or particular places within the target areas. Pull intel from a variety of sources to interpret the relevance of risk factors at risky places and at certain times. Consider the possibility that different policing actions can have the best effects in some places, but not others, depending on the nuances of these places and their situational contexts. 4. Actions that are done in a target area should clearly relate to the intervention strategy directed at specific risk factors. 5. Expect that risk factors may become less risky over time. The risk from landscape features should abate over time as a result of the intervention. For this to be measurable, a clear accounting of what the intervention actions did to reduce risk should be articulated as part of the implementation plan. Routinely reassess the meaningfulness of target areas, risk factors, and intervention strategies – they may need to change along with the dynamic nature of illegal behavior and crime patterns that are responding to the intervention activities. 6. Let the IPIR inform the intervention and the intervention results inform subsequent analyses to better the “next round” of intervention activities. Spatial or temporal lags might result in longer term impacts to lower risk places earlier in the intervention period, while higher risk places may need more time to respond to the point where long-term effects are measurable. 7. Plan interventions so that you can measure outcomes reliably. This is important because you’ll want to be able to repeat the effect next time you respond to a similar problem. That should be the essence of problem-oriented policing and risk management. If crime counts reduced and you can attribute it directly to your intervention activities, then you not only get the credit for success, but you know what to do next time the problem occurs. If your intervention strategy did not have the desired result, then you have a foundation for improving it next time. Once you get it right, you can repeat it. In a meta-analysis they performed on 11 intervention programs, Braga and Weisburd [1] report that decreases in crime related not only to the offender-centric strategies but also to steps taken to modify the environments in which they operate. This finding, and others presented by several authors of spatial research, complement psychological studies that reveal how treatments focused on people to change behaviors only works on behaviors that people do not do frequently. If people do the behavior enough in the same setting, the physical environment (itself) shapes the human behavior (even unconsciously). Psychologists refer to this as "outsourcing” control of behavior to the physical environment. When the environment consciously or unconsciously influences behavior, the only way to change human behavior for the long-term is to alter the environment and/or the action sequences. Research suggests this will have the best probability of changing outcomes [2, 3].

You might ask: What, specifically, about environments should be altered at high crime areas? This question brings to mind police and other stakeholders' efforts at 'crime prevention through environmental design' (CPTED). Altering the physical design of communities in which humans reside and congregate is a main goal of CPTED. However, CPTED without RTM is like playing darts blindfolded (and not even knowing if you are in the right room before you throw). Don't engage in CPTED blind when RTM can provide some actionable intel for guidance. Risk terrain modeling diagnoses the environmental features that need to be mitigated in order to reduce crime over the short and long terms. All over the world, police use RTM to identify risks that come from features of a landscape and model how they co-locate to create unique behavior settings for crime. RTM produces intel (and an evidence-base) that informs decisions about WHAT to do WHERE and WHY to do it. RTM also informs strategies and policing operations that can go well beyond CPTED. It helps to identify and eliminate spatial influences of risky features of a landscape without having to demolish or reconstruct physical infrastructures. Legal scholars endorse RTM as one of the few methods of intelligence-led policing that respects Constitutional protections (see: www.riskterrainmodeling.com/action-policing.html). Risk reduction strategies informed by RTM can accommodate the ideas of CPTED in targeting certain locations for intervention, but they extend beyond situational crime prevention and opportunities for crime or a "crime triangle", and, instead, target all aspects of the context that raises the risk that crime will occur. RTM provides an approach to understanding crime occurrence by identifying the relative influences of environmental factors that contribute to it; risk terrain maps inform decisions about which places or areas can be targeted to reduce these risks. RTM provides a way in which the combined factors that contribute to criminal behavior can be targeted, connections to crime can be monitored, spatial vulnerabilities can be assessed, and actions can be taken to reduce worst effects in cost-effective ways. The key to utilizing RTM successfully is to start using it. Click here to learn how to get started. Footnotes: 1. Braga, A. A., & Weisburd, D. (2010). Policing problem places: Crime hot spots and effective prevention. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2. Louiselli, J. K., & Cameron, M. J. (Eds.). (1998). Antecedent control: Innovative approaches to behavioral support. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. 3. Kennedy, L. W., & Forde, D. R. (1998). When push comes to shove: A routine conflict approach to violence. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. |

|

|

riskterrainmodeling.com is maintained by the Rutgers Center on Public Security (RCPS). It is the official website of Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) research and resources, based out of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed