Features of a landscape can influence and enable behavior. Consider a place where children repeatedly play. When we step back from our focus on the cluster of children, we might realize that located where they play exists swings, slides and open fields. These features of the place (i.e. suggestive of a playground) attract children there instead of other locations that are absent such entertaining qualities. In a similar way, spatial factors can influence the seriousness and longevity of crime problems. (These children aren’t criminals; the analogy is benign in that respect). What risk terrain modeling (RTM) does is to identify the risks that come from features of a landscape and model how they co-locate to create unique behavior settings for crime.

You can probably imagine the clichéd “dark alleyway” when thinking of crime victimization. In this case, you are considering at least two attributes of a landscape: (1) an alleyway and (2) poor lighting. The risk of crime is thought to be exceptionally high at places where these particular attributes coexist. What we’ve found through scientific research is that the risks that manifest specific features of a landscape, and their interaction effects, can be used to compute a probability of criminal behavior occurring. RTM creates this composite model of spatial vulnerabilities to crime at micro places.

The RTM process begins by selecting and weighting factors that are geographically related to crime incidents. Then a final model is produced that basically 'paints a picture' of places where criminal behavior is statistically most likely to occur. We say crime as the outcome event because that’s what we have primarily studied. But, we know of RTM being used for other topics, such as urban planning, injury prevention, public health, traffic safety, pollution, or maritime piracy.

The reason RTM is used by practitioners across many disciplines is because it was originally developed to solve a problem that we all equally face: how to leverage data and insights from various sources, using readily accessible methods. As applied researchers, we know that other people like us have expended considerable effort, over many decades, to identify links between certain factors and particular crime outcomes. In 2009, we wanted to simultaneously apply all of these empirical findings to practice. RTM was developed as a framework to make this integration happen: We synthesized evidence-based insights and disparate data sources by using geography as their common denominator. Risk terrain modeling was born.

RTM methods have been adopted by academic colleagues and public safety practitioners from around the world including Chicago, New York, Paris, Milan, and Bogotá; RTM is used on every continent on Earth (except Antarctica, as far as we know!). We are also aware of a growing body of peer-reviewed journal articles by authors unaffiliated with us who have utilized RTM methods. Combined with our own published research, there is a wealth of rigorous scientific evidence to show that RTM works and is an invaluable tool for spatial risk analysis.

It’s no secret that location matters. The question is: how do you utilize data that you currently have to assess spatial risks and prevent undesired outcomes? RTM helps in this process. RTM is by all intents-and-purposes a diagnostic method. With a diagnosis of the environmental correlates of certain behaviors or outcomes, you can make very accurate forecasts.

With knowledge of spatial risk factors, intervention activities can be designed to suppress crime in the short-term and mitigate the risk factors at these areas so they are less attractive to criminals for the long-term. For instance, in one National Institute of Justice (NIJ) study, a 42% (statistically significant) reduction in robberies was achieved by focusing on environmental features of high-risk places, not merely the people located there. With RTM, you can prioritize risk factors and prescribe actions to mitigate these factors, even within the confines of limited resources. RTM has been shown to do this for a variety of crime types in different settings.

Hotspots tell you where crime is clustering, but not necessarily why. All too often people focus on hotspots without giving equal consideration to the spatial attributes that make these areas opportunistic in the first place. While there are social, situational, political, cultural, and other factors related to the variety of crime outcomes, there is also a spatial component. Hotspots are merely signs and symptoms of places that are highly suitable for crime. RTM advances this by providing the spatial diagnosis.

You can probably imagine the clichéd “dark alleyway” when thinking of crime victimization. In this case, you are considering at least two attributes of a landscape: (1) an alleyway and (2) poor lighting. The risk of crime is thought to be exceptionally high at places where these particular attributes coexist. What we’ve found through scientific research is that the risks that manifest specific features of a landscape, and their interaction effects, can be used to compute a probability of criminal behavior occurring. RTM creates this composite model of spatial vulnerabilities to crime at micro places.

The RTM process begins by selecting and weighting factors that are geographically related to crime incidents. Then a final model is produced that basically 'paints a picture' of places where criminal behavior is statistically most likely to occur. We say crime as the outcome event because that’s what we have primarily studied. But, we know of RTM being used for other topics, such as urban planning, injury prevention, public health, traffic safety, pollution, or maritime piracy.

The reason RTM is used by practitioners across many disciplines is because it was originally developed to solve a problem that we all equally face: how to leverage data and insights from various sources, using readily accessible methods. As applied researchers, we know that other people like us have expended considerable effort, over many decades, to identify links between certain factors and particular crime outcomes. In 2009, we wanted to simultaneously apply all of these empirical findings to practice. RTM was developed as a framework to make this integration happen: We synthesized evidence-based insights and disparate data sources by using geography as their common denominator. Risk terrain modeling was born.

RTM methods have been adopted by academic colleagues and public safety practitioners from around the world including Chicago, New York, Paris, Milan, and Bogotá; RTM is used on every continent on Earth (except Antarctica, as far as we know!). We are also aware of a growing body of peer-reviewed journal articles by authors unaffiliated with us who have utilized RTM methods. Combined with our own published research, there is a wealth of rigorous scientific evidence to show that RTM works and is an invaluable tool for spatial risk analysis.

It’s no secret that location matters. The question is: how do you utilize data that you currently have to assess spatial risks and prevent undesired outcomes? RTM helps in this process. RTM is by all intents-and-purposes a diagnostic method. With a diagnosis of the environmental correlates of certain behaviors or outcomes, you can make very accurate forecasts.

With knowledge of spatial risk factors, intervention activities can be designed to suppress crime in the short-term and mitigate the risk factors at these areas so they are less attractive to criminals for the long-term. For instance, in one National Institute of Justice (NIJ) study, a 42% (statistically significant) reduction in robberies was achieved by focusing on environmental features of high-risk places, not merely the people located there. With RTM, you can prioritize risk factors and prescribe actions to mitigate these factors, even within the confines of limited resources. RTM has been shown to do this for a variety of crime types in different settings.

Hotspots tell you where crime is clustering, but not necessarily why. All too often people focus on hotspots without giving equal consideration to the spatial attributes that make these areas opportunistic in the first place. While there are social, situational, political, cultural, and other factors related to the variety of crime outcomes, there is also a spatial component. Hotspots are merely signs and symptoms of places that are highly suitable for crime. RTM advances this by providing the spatial diagnosis.

|

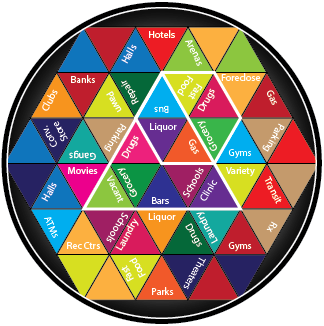

Research proves that the spatial dynamics of crime are not the same in different settings, even for the same type of crime. A limitation of traditional approaches to crime analysis is the assumption that standard patterns of crime will be seen across environments. This is not the case. Think about it through the analogy of a kaleidoscope: The kaleidoscope itself represents a particular jurisdiction; The shards of glass represent crime attractors, or features of the landscape, such as bars, fast food restaurants, grocery stores, etc. Moving from jurisdiction to jurisdiction represents a turn in the kaleidoscope. With each turn, the shards of glass come together in different ways, creating unique spatial and situational contexts that have implications for behavior at those places. With this framework in mind, it is not safe to assume that a “standard” response to crime problems will provide similar returns across all environments. RTM is needed to articulate these unique spatial dynamics of crime within jurisdictions.

|