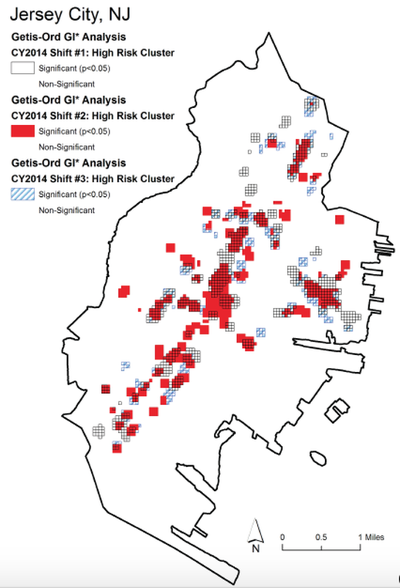

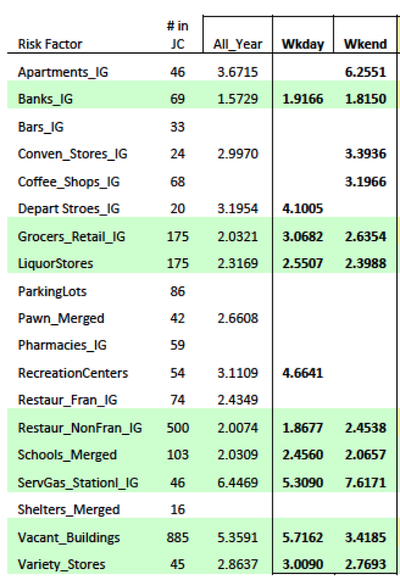

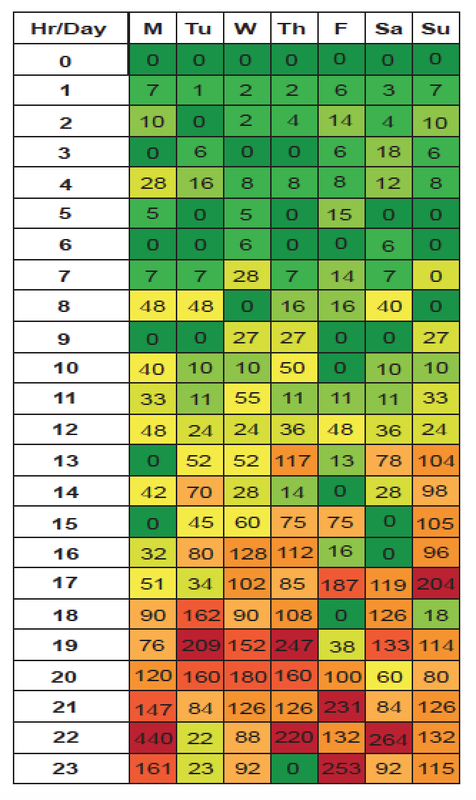

Grubesic and Mack (2008) argued that we cannot treat space and time as independent entities, but, rather, as interdependent ones that interact to create situational risks. The interactions among people and their geographies are deeply fluid in the sense that no feature retains its “social relevancy” permanently (Kinney, 2010, p. 485). Places can be “fantastically dynamic” (Jacobs, 1961/1992; p. 14). Basically, places can have different risks at different times because a criminogenic feature of the landscape can have varying spatial influences depending on its social relevancy at different times and under particular circumstances (e.g. Gaziarifoglu, Kennedy, & Caplan, 2012; Irvin-Erickson, 2014; Yerxa, 2013). The RTM approach allows not only an assessment of risk factors at certain places, but an ability to judge their effects at different times. To do this with the RTMDx Utility, simply prepare your data by first (1) isolating crime incidents (i.e. the events you wish to study) that occurred within the time period(s) of interest to you. Then (2) produce risk terrain models for each of the temporally different datasets. For example: create three shapefiles of robberies that occurred between 7pm-3am, 3am-11am, or 11am-7pm, respectively. Then, use these three datasets to run three different risk terrain models. Something similar can be done to study risky places for crimes occurring on the weekend vs. weekdays; daytime vs. nighttime hours; school year vs. summer months; sporting (home) game days vs. (away) game days; etc.

* Glossary (see the full RTM glossary, here)

For references, see Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; UCPress), by Caplan & Kennedy.

Criminologists have long sought to explain why crime occurs at certain places and times. These inquiries have led to observations and documentation of many different factors that contribute to the spatial and temporal dynamics of illegal behavior and crime victimization. Victims and offenders have been considered in various contexts, formed by both the activities that individuals pursue but also by the nature of the environments they occupy. Some places, we know, are more likely to be locations of crime than others. That is, where exposure to crime events is relatively high. This may be the case because of the characteristics of people who frequent these places or it may have something to do with the qualities of the environments themselves. Of course, both of these can vary by time of day, week, or year. If we concentrate on the characteristics of places, we can focus on factors that are conducive to crime occurrence, offering a means by which to target certain places that are more likely to promote illegal behavior.

Multiple approaches to studying spatial crime risks have merit, and have helped create a more complete picture of the underlying processes that contribute to crime occurence. Analytical models are tools for the acquisition of knowledge. "Knowledge," said Daryl Morey, the man hired to empirically minimize uncertaintly in basketball, "is anything that increases your ability to predict the outcome" [1]. Predictive crime models allow criminologists to explore attributes that lead to crime outcomes, and to determine how much weight to give to each. Having prediction models without any human opinion can force people to ask the right questions. Models may not be the "right" answer so much as the "better" answer, and, thus, can lead to better and more insightful questions. Crime prediction needs more than big or little data. It needs people and experts. Crime prediction models must, at some point, invite human judgement into decision-making processes. The task of the criminologist is not simply to explain empirical results via theory or opinion, but to provide actionable prescriptions for how to use knowledge to combat crime and its consequences. The task of the criminologist is to facilitate and moderate human judgements into decision-making. The talent of a skilled criminologist is to listen to both empirical evidence and subjective human judgement, and to blend the two. A person's understanding of what is seen or heard changes with the context in which each is aquired. The criminologist's mind needs to be in a constant state of defense against all the junk that's trying to mislead it, and to relate context to data without being overwhelmed by the context of data. The criminologist's task is to communicate meaning out of the signals and noise, and to soundly advise how to monitor connections to crime, how to assess spatial vulnerabilities, and how to act in order to reduce the worst effects of their predictions. Post inspired by Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; UCPress), by Caplan & Kennedy and by "The Undoing Project" by Michael Lewis. Endnote from pg. 31 of "The Undoing Project" by Michael Lewis. |

|

|

The official website of Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) research and resources, based out of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed