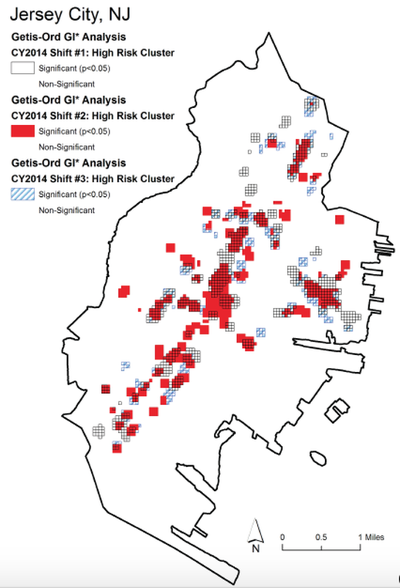

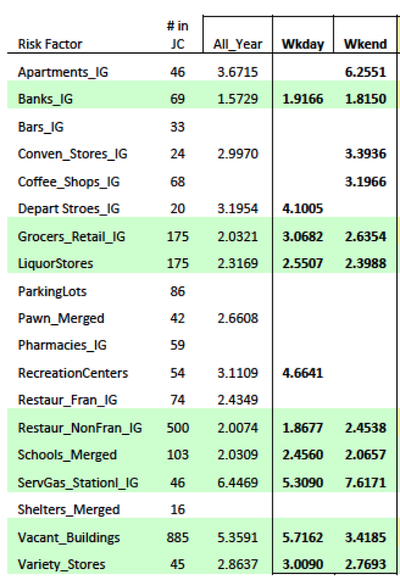

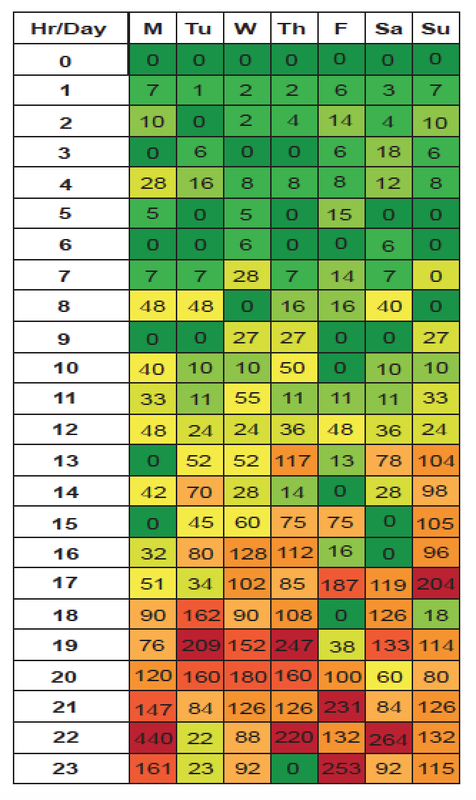

Grubesic and Mack (2008) argued that we cannot treat space and time as independent entities, but, rather, as interdependent ones that interact to create situational risks. The interactions among people and their geographies are deeply fluid in the sense that no feature retains its “social relevancy” permanently (Kinney, 2010, p. 485). Places can be “fantastically dynamic” (Jacobs, 1961/1992; p. 14). Basically, places can have different risks at different times because a criminogenic feature of the landscape can have varying spatial influences depending on its social relevancy at different times and under particular circumstances (e.g. Gaziarifoglu, Kennedy, & Caplan, 2012; Irvin-Erickson, 2014; Yerxa, 2013). The RTM approach allows not only an assessment of risk factors at certain places, but an ability to judge their effects at different times. To do this with the RTMDx Utility, simply prepare your data by first (1) isolating crime incidents (i.e. the events you wish to study) that occurred within the time period(s) of interest to you. Then (2) produce risk terrain models for each of the temporally different datasets. For example: create three shapefiles of robberies that occurred between 7pm-3am, 3am-11am, or 11am-7pm, respectively. Then, use these three datasets to run three different risk terrain models. Something similar can be done to study risky places for crimes occurring on the weekend vs. weekdays; daytime vs. nighttime hours; school year vs. summer months; sporting (home) game days vs. (away) game days; etc.

* Glossary (see the full RTM glossary, here)

For references, see Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction (2016; UCPress), by Caplan & Kennedy.

Comments are closed.

|

|

|

The official website of Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) research and resources, based out of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed