|

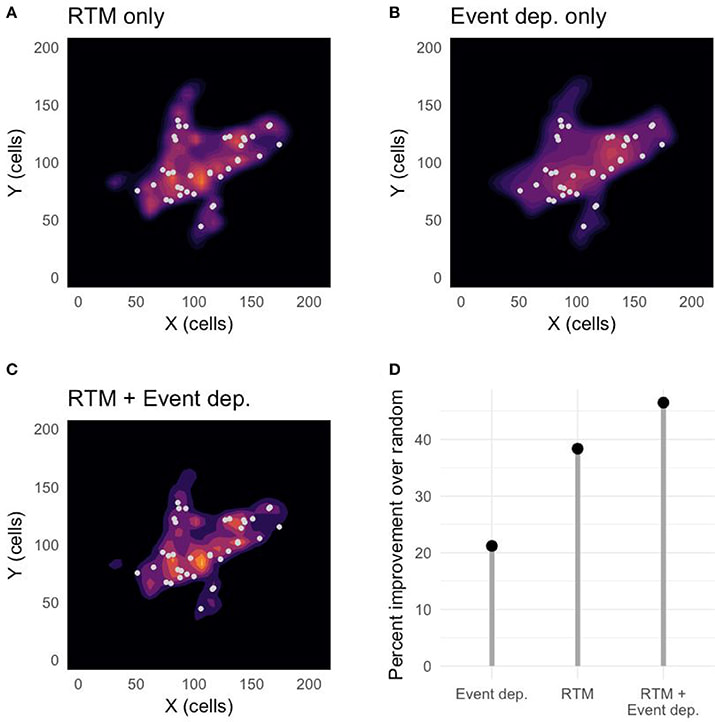

The new article, "Predicting Dynamical Crime Distribution from Environmental and Social Influences", published in Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics finds that combining risk from exposure (past events) and vulnerability (environment) when modeling crime distribution can improve crime suppression and prevention efforts by providing more accurate forecasting of the most likely locations of criminal events. As shown in the graphic below, Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM), as a measure of spatial vulnerability to crime, outperforms event-dependent methods (I.e. recent past exposures, such as hot spots or near repeats) as a predictive analytic. But, more importantly, a combined vulnerability-exposure measure outperforms both solo methods. By large margins. This would be expected according to the Theory of Risky Places. All models tested in the Frontiers article perform better than random, with the composite model performing better than the RTM-only model and the event-dependence-only model, in that order. The RTM-only prediction is roughly 70% better than the event-dependent prediction (I.e., hot spot, near repeat). And the composite model prediction is more than 100% better than the event-dependent prediction.

One take-away for researchers is that it’s important to consider the impact of the physical environment and how it influences outcomes resulting from human interactions at places. Since at least 1997 Abbott has claimed that "no social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social space and time…" He is correct. And, as such, requires researchers to operationalize more than just "crime counts" or "hot spot maps" as variables (or co-variates) in their statistical models. For instance, when researchers in Little Rock, AR used RTM to develop an aggregate risk of crime measure that they analyzed alongside a concentrated disadvantage index value, they produced a model that explained 55% of variation in neighborhood violent crime rates. This is no small feat considering that Weisburd and Piquero have commented that most criminal justice research does not often explain variations in crime by more than 20%. For practitioners, this reaffirms the call to go farther than merely mapping and then policing hot spots. Hot spots are just signs and symptoms of environments that are highly suitable for crime, but they offer very little insights for solutions to manage crime problems. RTM adds a spatial diagnosis. By combining Risk Terrain Modeling with hot spot analysis, you learn where to go and what to focus on when we get there. You add the why to the where. And as the research proves, interpreting crime vulnerabilities and exposures together makes the best forecasts, regardless of whether crimes persist, displace, or emerge at places where they have not happened before.

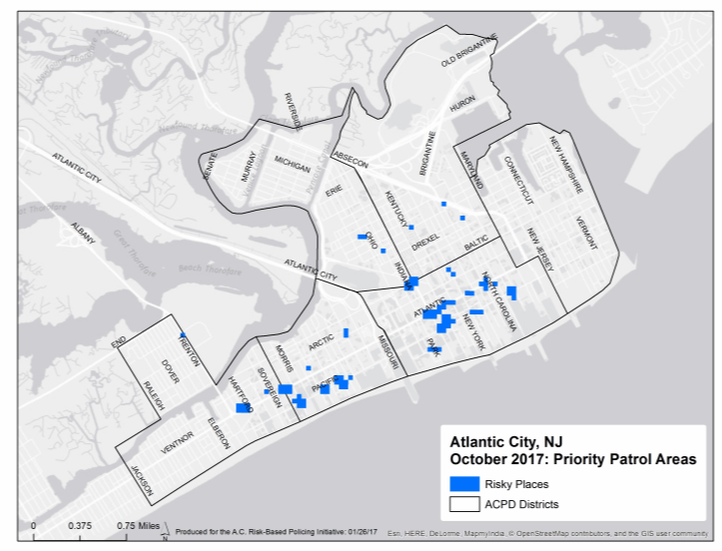

Bringing the vulnerability-exposure framework into professional practice ensure that you offer police (or other stakeholders) a unique opportunity to suppress crimes immediately by allocating resources to existing problem areas, and to initiate prevention strategies at the most vulnerable (high-risk) places within hot spots. This form of risk-based policing, whereby interventions are focused on the spatial attractors/generators of crime at priority places is discussed in detail (with lots of case studies) in this forthcoming book. Additional information and research evidence can be found at www.rtmworks.com.

So, in a nutshell: Risk Terrain Modeling is a best-practice that does not have to replace existing practices. It complements them to enhance crime analysis and to produce actionable intelligence for police commanders that want to be efficient and effective problem-solvers. Comments are closed.

|

|

|

The official website of Risk Terrain Modeling (RTM) research and resources, based out of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed